Back in New Jersey on August 21, 1949 I saw my first Loggerhead Shrike. It was my Life Bird #119. Actually, a few days earlier I had found grasshoppers impaled on the spikes of a barbed wire fence in the Passaic River bottomlands a short walk from my home in Rutherford.

I had read about how the "Butcher Bird," whose "weak feet" lacked the talons of raptors, must stabilize its victims in this manner to permit them to be torn apart with its hooked beak. Hoping one day to see mice and small birds in a shrike's larder, I did not expect lowly insects. I searched for the shrike to no avail until three days later, when I caught sight of my "lifer."

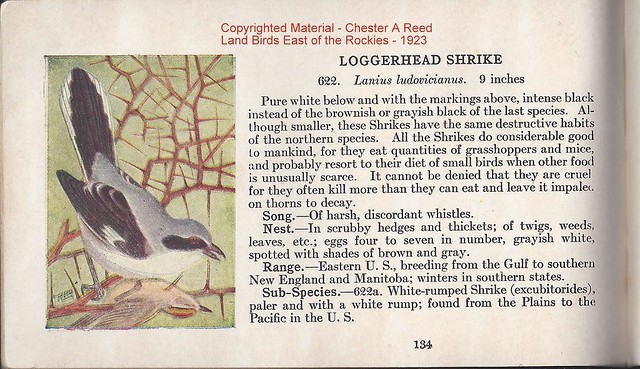

I did not know exactly what to call the bird, as nomenclature was confusing. My tattered little pocket Chester A Reed guide (published in 1923) called it a "Loggerhead Shrike." In those days birds were considered to be either "good" or "bad," but in Reed's opinion the shrike seems to straddle the line.

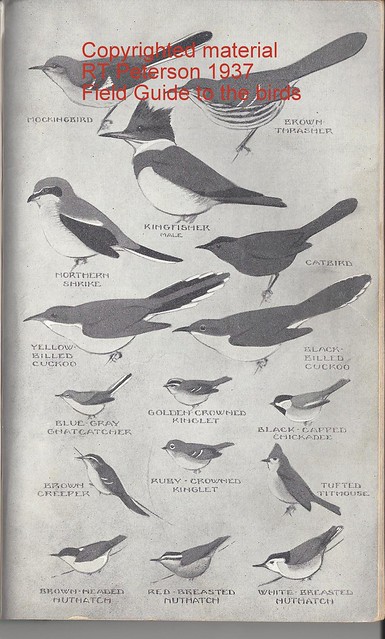

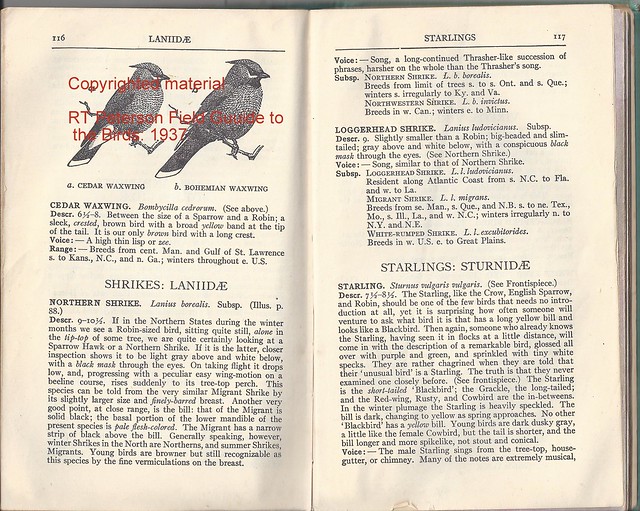

More up-to-date, my 1937 Peterson Field Guide to the Birds only illustrated the larger (and even less common) Northern Shrike:

The text was not very illuminating, as it gave short shrift to the Loggerhead or Migrant Shrike as it was called:

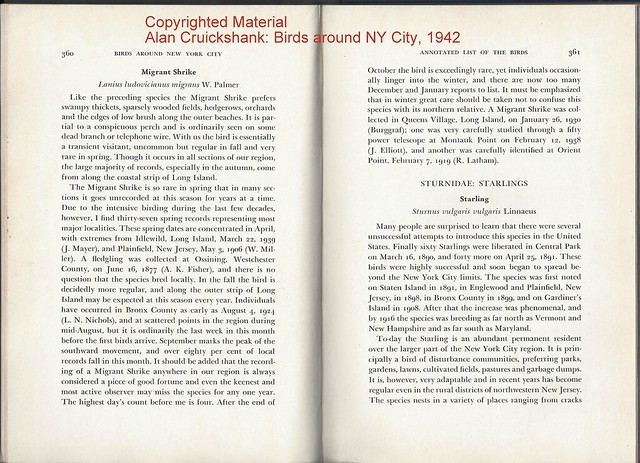

My "go to" reference for information about distribution and abundance was Allan Cruickshank's "Birds Around New York City (1942). I was elated that I had seen a relatively rare bird. Cruickshank reverted to calling it a "Migrant Shrike."

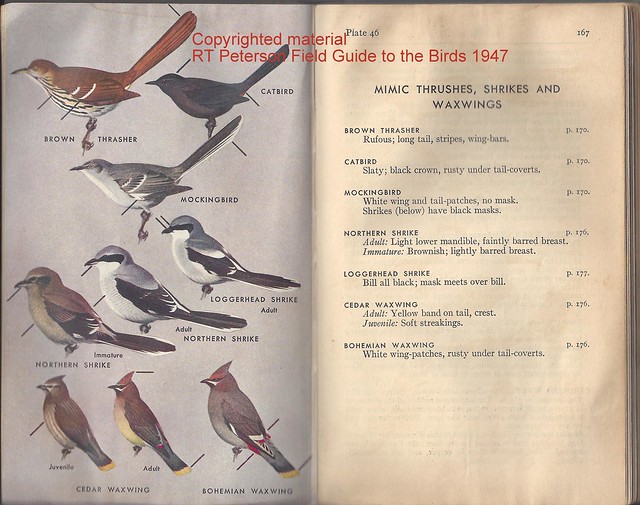

Only later, during the year of my first sighting, did Peterson's 1947 Guide appear, with the Loggerhead Shrike in all its glory.

During the 20 years following my sighting, the Loggerhead Shrike became more common in New Jersey, especially in the southern reaches of the state. However their numbers decreased and they once again became quite rare towards the end of the 20th Century up to the present. Ingestion of pesticides in insect prey is strongly suspected as the cause of their drastic decline. In south Florida, now my home, they are quite common breeders and winter visitors.

Cold light brings out the blue:

Their prey is varied, but mostly insects. I think this huge grub is a horsefly larva.

Except during the breeding seasons, Loggerhead Shrikes tend to be solitary. They often select the highest perch...

...and may be challenged by grackles...

...mockingbirds...

...and Blue Jays. In this case, the shrike retreated, possibly to simply avoid the company of others.

Yet, many time I have seen a shrike sit peacefully with a variety of other species, such as this American Kestrel...

...or a Northern Flicker.

One of my more remarkable shrike images includes two shrikes with a Belted Kingfisher and a kestrel, in late November.

In June the shrikes are courting.

I usually find it difficult to get any closer than 30-40 feet from a Loggerhead Shrike, but this fledgling was an exception.

The shrikes like to hunt for lizards on our back patio, so I can get some close views through the glass doors.

Parents watched this youngster as it unsuccessfully pursued a Brown Anole. They did not intervene, perhaps to teach their fledgling the importance of stealth and persistence.

a very well-informed series Kenneth. It was interesting to see the differences between your/our butcherbirds. I also noted your reference to 'cold light' and hadn't thought of that before (learn something every day.). The belted kingfisher up on the power lines too is something special.

ReplyDeleteAn interesting post. Australian butcherbirds apparently spike their prey also, although I haven't actually seen it. The outline shape is roughly similar too. The Grey Butcherbird has an attractive call too.

ReplyDeleteShrikes are really cool birds. The grey and black make for a very striking bird. I remember seeing a Northern Shrike stalk and kill a vole before my eyes in Minnesota this winter.

ReplyDeleteExcellent post filled with interesting information and wonderful photographs! I especially love the image of the shrikes, kingfisher and kestrel ... FANTASTIC!

ReplyDelete